Eulogy delivered by John Crawshaw at Milton Crawshaw's funeral on 7 January 2016 at Macquarie Park, Sydney.

Click on images to enlarge.

Good morning everyone.

On behalf of the immediate family I'd like to bid you welcome to this occasion, to remember the life and times of our father, husband, grandfather, great-grandfather, uncle, great-uncle..., Milton Crawshaw, and to lay him to rest.

First of all, thank you all for coming here today. Our father was a quiet unassuming man, no great extrovert, and yet it's clear that his life - his very, very long life - touched on the lives of many about him. So we are pleased to see you here in such large numbers to celebrate his life.

The Prime Minister says “there has never been a more exciting time to be an Australian”. I think beyond a shadow of a doubt we can say the lifetime of our father spanned the most exciting century in the history of humanity. And at times its most gruesome.

Milton was born in December 1912, before the First World War, in a world very different from the one we know today. The population of Australia was under 5 million. Not only were there were no mobile phones or computers, no television or radar; rudimentary motor cars, telephones and aeroplanes were the playthings of the rich. Most people lived pretty much as they had in late Victorian times but these technological marvels (and war) were about to revolutionise everything.

There were, however, newspapers and our father's earliest memory was seeing the photos of soldiers killed in the Great War and feeling frustrated that he could not read the attached articles. He was not yet six years old when the war ended in November 1918. His own uncle was killed in the trenches of the Somme towards the end of the war; and an aunt living in the same house died of the Spanish flu the following year (1919); so the family was touched by the tragedy of the war and its aftermath.

As an aside, if 62,000 young Australian men were killed (to say nothing of those maimed in body and mind) out of a population of 5 million, that would be the equivalent today of sending off nearly 300,000 men to their deaths in a foreign war. Would the country stand for it? These are things we ponder in these centenary years. But the resentment against Germans was a key factor in the next part of the story, while our father was still an infant.

Many of you – perhaps most of you – may know that our father was not born with the English surname Crawshaw, but the German surname Kraushaar (curly hair). By my calculation, he was only 1/32 German: the other 31/32 were of English stock with a smattering of Scots. (In fact his oldest Australian ancestors were a Scottish couple with the unlikely names of John and Mary Smith who arrived as free settlers just 10 years after the First Fleet.)

By a quirk of fate the German surname had come down the male line from a weaver called Johann Conrad Kraushaar (my namesake!) who moved from Germany to the East End of London in about 1760 and married the daughter of German immigrants from Hamburg. They were all founding members of the German-speaking Lutheran church in East London at that time. Our father's grandfather, Alfred, migrated to Australia in 1881. Our father's father, Conrad, was born in Woolloomooloo in 1885.

By the time of World War I, Alfred and his sons were running a confectionery business in Sydney with a number of shops in the city and inner west. The shop windows carried the name A. Kraushaar & Sons. As you can imagine, anti-German sentiment was running very high and members of the public would express their feelings outside the shops (some say bricks were thrown). So though the family had had no connection with Germany for over 150 years, and certainly nobody spoke a word of German, they (like the British royal family) deemed it prudent to change their name, choosing an English surname that sounded similar to the original German one.

So our father's paternal grandfather was Alfred Kraushaar; his mother's surname was Lister: hence he was Milton Alfred Lister Crawshaw. His mother's relatives, the Listers and Toms, were pioneering families in the Central West of NSW and were associated with the discovery of gold in the Orange district in 1850. That is a long story and we have very little time. There are family websites that recount that story.... His Glasson relatives still farm in the area.

In recent years, our father wrote and dictated a series of reminiscences; I have some extracts here to help me keep the story straight...

Milton was born in December 1912 over one of the confectionery shops in Darling St., Rozelle. They stayed there until he started school across the road. He remembered they kept a horse in the back yard who was hitched up to a cart during the week to make deliveries of sweets; out of hours he used to ferry the family around in a sulky.

By the early 1920s his father had purchased a Model T Ford truck and was selling his sweets down the south coast while his brothers ran the factory in Darlinghurst. Rather than leave the family alone in Sydney all week, in December 1922 he decided to move the family to Thirroul and make a weekly trip up to Sydney for supplies.

So between the ages of 10 and 17 our father lived in Thirroul. The house is still standing; money was tight and the cow and chickens on the spare block of land next door helped keep them fed. He often used to accompany his father on business trips and learned to drive at the age of 12 on his father's truck. He was allowed to drive from the top of the Bulli Pass along the unsealed road as far as Sutherland where they would finally find some traffic.

Our father completed the Leaving Certificate at Wollongong High School at the end of 1929 and also obtained his driver's licence when he turned 17, so that, while deciding on a career, he was able to drive the truck alone to Sydney for supplies.

This was, of course, at the start of the Great Depression. So while investors were throwing themselves out of tall buildings on Wall St., young Milton had finished high school and was looking for his first job. The following years were very hard for everyone and money was scarce. This experience turned him into a frugal "small footprint person". He would never use more resources than necessary to get the job done. "Waste not, want not" was his motto. He was a saver rather than a spender: indeed, conspicuous consumption was anathema to him.

He would have liked to study medicine but the family could not afford to keep him for all those years of study, so he settled on pharmacy, which allowed him to earn some money as an apprentice while he studied part-time. He found an apprenticeship in Northbridge and, since the family was still living in Thirroul, he boarded for four years from 1930 with an uncle and aunt in Mowbray Road, Lane Cove.

While attending Sydney University he would ride his bike from Lane Cove to Northbridge early in the morning, then take the tram to Milsons Point, a ferry to the Quay and another tram to the university. He would work all afternoon in the pharmacy in Northbridge, then cycle home to Lane Cove. During this period (1931/32) he watched progress on the Harbour Bridge as it was being built from both ends: it was completed in March 1932. (And opened by De Groot on 19 March.)

He became a registered pharmacist at the age of 21 (the minimum: he had completed all his exams earlier but had to wait to “come of age”) and continued working at the Northbridge Pharmacy, boarding for four years just a few hundred metres from the shop. (He worked in that shop for 35 years and claimed to have hated every minute of dealing with customers!) In 1938 he found a house for the family in Cammeray and they moved back to Sydney. He stayed another four years with them there. At this time he bought the pharmacy from his old boss.

When World War II broke out he went through the call-up procedures. Pharmacists were taken in as lieutenants, doctors and dentists as captains. He was told they didn't need any more pharmacists and to go back to his shop and they would let him know if he was wanted. This rather disappointed him as he would have liked to work with field doctors and learn their trade with a view to studying medicine after the war.

In November 1943 he married Mary Johnston whose family also attended the North Sydney “meeting” of brethren. By 1949 they had three young boys.

Our father always had itchy feet. He began travelling the world long before it became fashionable. In 1949 (when his third child - Yours Truly! - was just a few months old) he had the opportunity to travel to Europe on an ex-war Dakota DC-3. To give you an idea of the times (and our father's memory for geography when dictating the story), it had to stop for refuelling in Cloncurry, Darwin, a remote island in the Arafura Sea, Manila, Hong Kong, Hanoi, Rangoon, Calcutta, Delhi, Karachi, Bahrain, Nicosia and Rome, before reaching its destination of Mulhouse in eastern France near the Swiss and German borders.

The plane was badly overloaded. Our father and another passenger had to sit in the cockpit to help distribute the weight and our father had to pull a throttle lever on take-off. Heroic times indeed!

He then travelled by train and ferry to England where he was interested to see some of the cricket grounds where Bradman's “Invincibles” had completed an Ashes whitewash the previous year. There was still much war damage and because food-rationing was still in place, he carried a suitcase full of tinned meat to distribute. He bought a car, drove it around the country and then shipped it back to Sydney while he took a steamer for New York; then a flight to Toronto, the Canadian Pacific railway to Vancouver, a flight to San Francisco; then by Pan Am to Hawaii, Fiji and back to Sydney in September 1949.

This was just the first of many overseas trips. In particular, in 1954 he packed up the whole family and his sister Hope and travelled by ship to Europe, buying a car and travelling around the British Isles and the Continent. This epic voyage lasted six months and left a lasting impression on all the participants, four of whom are here today.

As an inveterate traveller, even in the '70s and '80s he was going to uncommon places like Israel and Egypt and South Africa during apartheid. He told me in recent years that there were two places he regretted not having seen: East Berlin under the Communists... and Timbuktu!!

Our father took great interest in world news and (surprisingly) all sports, though nobody in the family remembers him playing any (except tennis as a young man on his uncle's court); and the nearest thing he had to a hobby was probably checking his rain gauge and recording all rainfall over many years. As a young man, his sporting hero was Donald Bradman. No doubt our father was also pleased to make his ton – and then some.

Indeed, the longevity of this generation is quite remarkable. You probably know that he had four sisters: Charity, Joy, Hope and Faith. Charity (known to us as Chattie, or Aunty Chat) recently died at the age of 104 years and 8 months; Joy died in 2012 at the age of 97; Hope is now 97 going on 98; Faith is 95. There must be some tough genes in there somewhere, as well as some clean living.

Our father leaves behind a widow, four children, nine grandchildren and, at last count, three great-grandchildren. Lots of young Australians and one young Italian (or Italo-Australian) who tells me she wishes she were here today to farewell her grandpa.

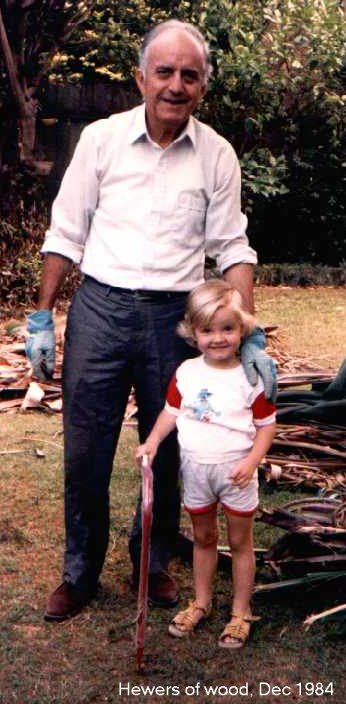

So our father, like the century, went through a series of phases in his life, as is exemplified in the photos in your order of service: it seems rather like Shakespeare's seven ages of man!

- As a child, he was photographed in a dress and long curls in the Victorian/Edwardian tradition. This was literally the horse-and-buggy era: indeed, he was thrown off the back of his father's horse-drawn cart on Pyrmont Bridge (fortunately onto a bag of chaff, or we might not be here today).

- Growing up, he used to spend his school holidays with his country cousins in the Bathurst-Blayney-Carcoar area, helping on the farm and shooting and skinning rabbits in-between times. It could be very cold and there was no running water but these were some of the best times of his life. His resilient generation rarely complained of hardship but got on with the job of bettering their lives. (I may add that one of these very close country cousins, his boyhood companion, was later killed in action in North Africa in WW II.)

- As a young adult he was something of a man-about-town, with sleek motor cars and clothes, travelling to New Guinea with friends, singing in a choir, and so on. As a matter of fact, he was always rather fond of motor cars: he always said he got his licence on his 17th birthday and after the age of 80 he had to have annual driving tests to keep that licence. On one occasion, he asked one of his examiners how old he was ?the answer was 65 - and he told him he'd been driving for more years than the examiner had been alive. He kept that licence until he was 100 and was driving until he was 99. When he turned 100, I offered to help him drive down the street just to say he had done it, but he declined. So that makes 83 years with a licence and a few years' driving before that.

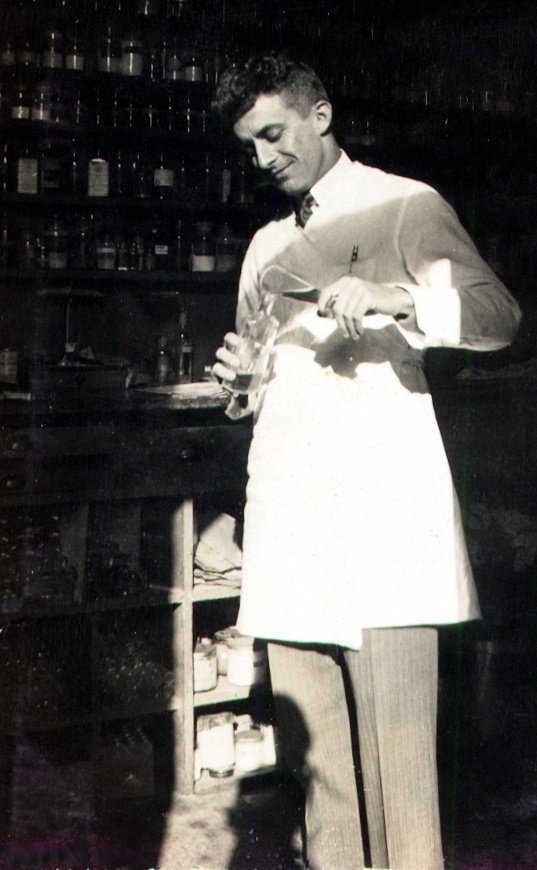

- He began work as a young pharmacist at a time before penicillin was available (it was first used in 1942) and the chemist had to make all his own medications and lotions. Some of us still remember him using a spatula to make ointments on a marble surface and measuring out the ingredients of liquid preparations (and the bottle of opium on the shelf for use in cough medicine); and he finished his career at the age of 84 filling scripts on computer and taking bottles of pills off the shelves that had been pre-packaged by the drug companies.

- After surviving the Depression and working extremely long hours, he was the dedicated family man and a committed member of his church: someone who spent a lot of time and effort preparing for services, who travelled and visited diverse church communities, who preached because he thought it was his duty to do so and who himself conducted many funeral services as we are doing for him today.

- In his later years, he did volunteer work, like Meals-on-Wheels, and dedicated a lot of time to his grand-children; but I think we'll be hearing from them next. At an advanced age, he learned to use email, and used to write regular emails to me in Europe recounting all the family's doings. This continued until after his 100th birthday.

So he was a religious man (or perhaps rather a spiritual man), a man of great integrity, a man who was inclined to live and let live, a true gentleman from another time, a man blessed with a prodigious memory, a man whose retiring nature probably somewhat obscured his intelligence.

As he used to say of his own father, he was a small man with a big heart: he will be sorely missed.